introduction

Next time you're diving in Malta and happen to see a little puff of purple, blue, or violet — look closer.

What you may be seeing is a Flabellina affinis, a sea slug no more than a few centimetres in length. This particular kind of sea slug is a nudibranch. Yes, sea slugs are related to our own land slugs. Just more colourful. And underwater.

If you look closely, you'll see a soft body covered in little white-tipped purple-ish tentacles, with two pairs of longer tentacles on one end.

In this article, I describe what one sees of this creature throughout its lifecycle. It's a guide to observation, not a scientific paper.

If you're aiming to observe the Flabellina affinis, be sure to take along a bright dive light and dial in your good trim.

Not only are the Flabellina small and easy to dislodge with improper finning, you'll want to light them up to see them in all glorious colouring. If you're taking pictures, take a strobe (or two) and macro lens. Otherwise everything will just be blue or green.

Note: all photos are from my Flabellina affinis tag gallery. They're licensed CC BY-SA 4.0 (i.e., free with attribution). Please attribute me, Kristaps, with a link to this page or domain. What follows are the last few Flabellina affinis photos from the site…

appearance

There might be more than one purple nudibranch in your area. How exactly does a Flabellina affinis look? Let's take a very close look.

Our subject here is about 3 cm. long — this species doesn't grow much longer than 5 cm. Say hello! Here's a guide to all the visible body parts.

- Tentacles are white-tipped, though for some specimens they're barely visible.

- The pair of long, ridged (annulate) tentacles are rhinophores. These are on the noggin.

- The long tentacles below the rhinophores are the oral tentacles; below that, the propodial tentacles.

- The other tentacles on the body are the cerata. Below their white tips is an opaque-ish violet ring. Below that, transparent with orange inside.

- The eye is the black dot below its right rhinophore.

- The mouth is between the oral and propodial tentacles.

The rhinophores, oral tentacles, and propodial tentacles are sense organs: their eyes are weak. The the oral and propodial tentacles are also used for movement or moving food.

Sometimes the cerata are clumped together; sometimes they appear separately and in nice rows.

The opaque-ish purple or blue ring below the white ceras tips is important!

There are several species that look similar. The Flabellina ischita, which is almost identical except that the cerata are transparent all the way to the tip, and the Edmundsella pedata whose rhinophores (front tentacles) are smooth, and the colour is more similar to the Fl. ischitana.

You can see all Flabellina ischitana and Edmundsella pedata photos elsewhere on this site. Both of these can usually be found in the same areas as the Flabellina affinis. To tell them apart, first make sure the rhinophores are annulated (ringed), and then, that the cerata are opaque. This can sometimes be very tricky, depending upon the light!

habitat and feeding

Like with most creatures, ourselves included…

The Flabellina affinis' habitat is strongly driven by the availability food.

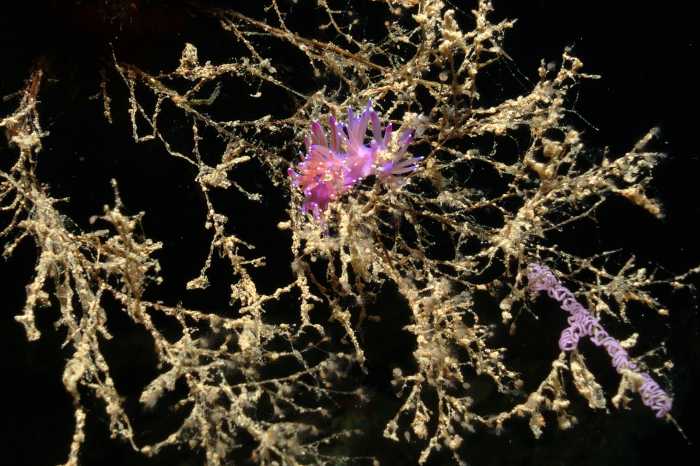

It feeds on a hydroid called Eudendrium racemosum; and wherever this is in abundance, surely you'll find the Flabellina. In fact, in almost all of these photos, you'll see the subjects in or among their food! Hydroids are related to jellyfish, but look like tufted sea vegetation.

I usually spot the Flabellina on shipwreck rails (interestingly, usually those on the far end facing away from shore), anchors, or pipes. But I can't tell if this is because they go where the food is, and the food is already there, or if the food is also elsewhere and there are other factors at play.

I most often see Flabellina at depths of 20–40 metres, but that could simply be because that's where most wrecks are in the area.

When open water diving, I'll spot the Flabellina clinging to anchors, rocky outcroppings, or other detritus in the water. Where there's one, there are probably others, so keep a sharp eye out!

reproduction

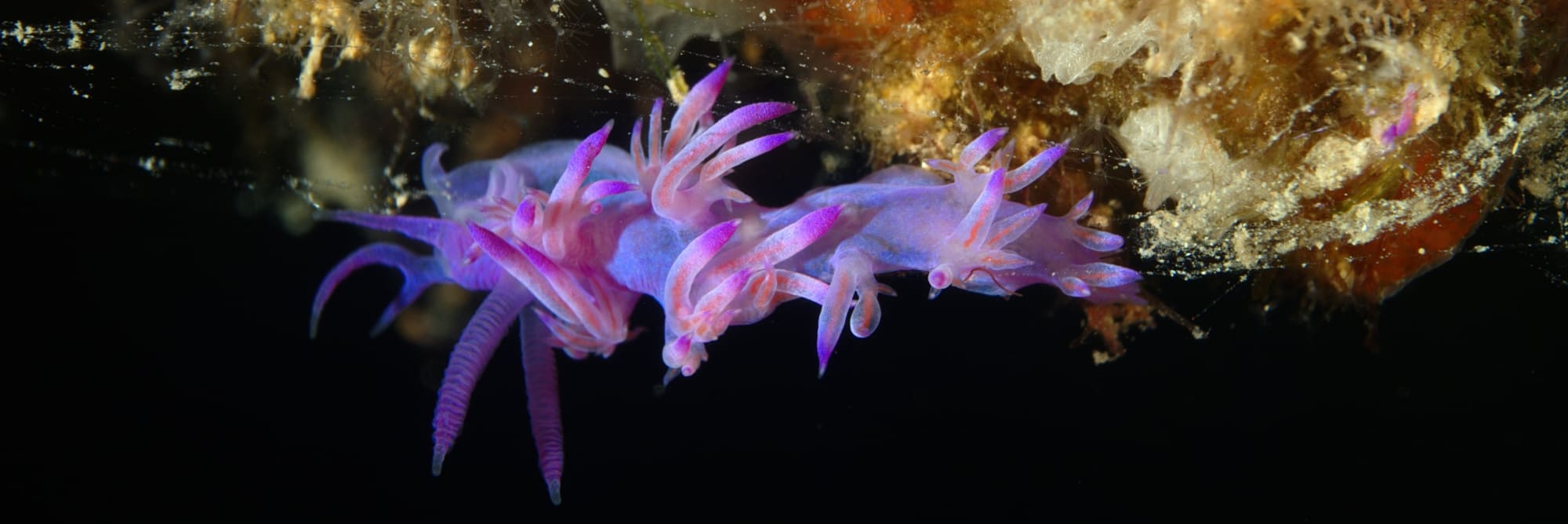

Sometimes I'll come across a Flabellina affinis and think to myself — what an enormous one! And it turns out… it isn't just one. It's at times difficult to tell a singular from a mating pair.

necklook like copepod parasites!

These nudibranchs aren't like humans, where a stork comes along and deposits babies. They're simultaneous hermaphrodites. So when it comes to sex, the male is defined as the subject who's able to penetrate the other's body wall with its penis. In fact, in the picture above you can see what might be a sperm deposit on the lower nudibranch, near the head.

I'm not sure how long it takes the eggs to grow, but…

Here we see an egg-heavy nudibranch.

The eggs are laid

in twists of purple that usually

hang on fronds of sea vegetation such as in the following

photo, lower right of the frame. Newly-laid eggs are

generally darker in colour than those that are ready for

hatching.

Over the course of a week or so, the egg sacs harden and lose colour, and eventually hatch nudibranch larvae.

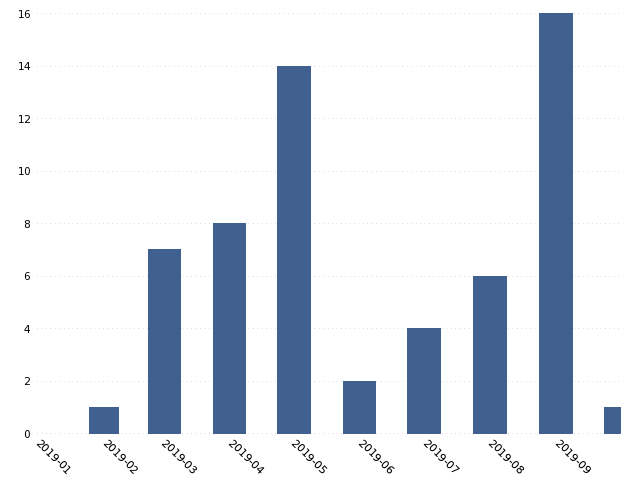

Using incredibly unscientific methods of just counting (not necessarily unique!) instances of the Flabellina in pictures, it seems that there's roughly quarterly life cycle. Note, in the following pictures, that my fidelity in picture taking is lacking earlier in time, as I did not have a macro lens yet.

At the moment (early September), there have already been many sightings, so the graphs looks like it will continue with a peak.

photography

The Flabellina affinis makes for amazing portraiture. Make sure that you bring powerful lights: at least a video light, but more appropriately a strobe. This will ensure that the species' brilliant colouring is fully retained.

I usually shoot with a 15x macro lens; however, I've been able to take almost as nice by simply shooting through my housing at full zoom. Even with a wide-angle lens and careful placement!

I'll often look for nudibranchs on rails and other

outcroppings so that I can freeze them

with a dark

background. The Flabellina affinis often will hang

out on fronds of its food, so it makes for excellent

photography where cutting out ambient light means a dark,

velvety background.

This is done by shooting with a very high shutter speed, entirely cutting out ambient light and relying on your strobes. On a DSLR, this usually means maximum strobe speed (usually 1/200 or so) stopped down to f/20 and above to keep the subject as much in focus as possible. This is the case for most macro, but the F. affinis is doubly great to photograph because it's colouring doesn't reflect (like, for example, the Cratena peregrina), so they're tolerant to over-powerful strobing.

It shouldn't need to be said, but I'm going to say it anyway because I know plenty of folks who've violated this rule.

Don't touch the nudibranchs. Don't move them around. Don't pose them.

Take your time and either move yourself or let the nudibranch move into frame itself. And enjoy!

references

I recommend the

sea

slug forum on the Flabellina affinis for

casual (but well-researched) questions.

For more detailed information, there's

Anja Schulze and Heiki Wägele's

Morphology, Anatomy and Histology of Flabellina

affinis (Gmelin, 1791) (Nudibranchia,

Aeolidoidea, Flabellinidae) and its Relation to

Other Mediterranean Flabellina Species

,

Journal of Molluscan Studies (1998), 64, 195–214.